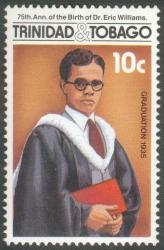

Trinidad & Tobago

“To educate is to emancipate”

When the first Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago was a child, his country was a British Crown Colony, and its government offered one university scholarship a year to the entire population. Young Eric Williams won it. Years later, on the eve of his country’s independence from Britain, he told the islands’ young people: “Yours is the great responsibility to educate your parents…you carry the future of Trinidad and Tobago in your school bags.”

Unfortunately, the religious groups, led by the Catholic Church, wanted to retain their grip on the country's educational system. They tried to hinder what they called “godless schools” — the state schools where Dr. Williams hoped to bring together the young people of the new nation.

The prospect of independence for Trinidad and Tobago threatened to end the tradition of mission schools. These were state subsidised, but “totally controlled” by each religion’s Denominational Board. Just before a crucial election the religious interests pressured the government to accept an education “concordat” which hampered government plans for school reform. A distinguished Trinidadian, Senator Professor John Spence, objects to the concordat giving the religious interests a veto over teaching materials in the denominational schools: “In a multi-religious democracy such as ours this is an untenable imposition in schools that receive public funding and which cater for students of all faiths.”

Church schools secure privileges before crucial election

The Concordat of 1960: Assurances for the Preservation and Character of Denominational Schools