From conversion to concordat

From conversion to concordat

Rome canonised the Viking king Olav for forcibly converting his countrymen to Catholicism. He thought the new religion would strengthen his position, but his successors found themselves taking orders from a distant pope who bound them with a concordat.

In 2011 a unique site was discovered beside a fjord in central Norway. The remains of a pagan temple were found in a field just 10 kilometres from the fortified town of the newly-christianised kings. A stone altar stood beside a wooden temple approached by a processional way of large stones. There the farmers gathered for sacrificial feasts of horses, cattle and other animals. They sprinkled the luck-bringing blood on the statues of their gods in the temple, on its walls and on each other. Then they boiled and ate the meat and toasted with ale to success in war, a good harvest and peace with the gods. [1]

In 2011 a unique site was discovered beside a fjord in central Norway. The remains of a pagan temple were found in a field just 10 kilometres from the fortified town of the newly-christianised kings. A stone altar stood beside a wooden temple approached by a processional way of large stones. There the farmers gathered for sacrificial feasts of horses, cattle and other animals. They sprinkled the luck-bringing blood on the statues of their gods in the temple, on its walls and on each other. Then they boiled and ate the meat and toasted with ale to success in war, a good harvest and peace with the gods. [1]

Towards the end of the tenth century, as one king after another tried to christianise central Norway, the site had been dismantled and carefully hidden. The heathen Norsemen took apart the wooden temple and buried the rest beneath a thick layer of peat. Then they must have placed the wooden statues of their gods in their longboats and sailed down the Trondheim fjord out to the open sea, perhaps to Iceland, like many before them. It is due to these religious refugees that the Icelandic sagas contain accounts of the forcible conversion of central Norway and even of the lost pagan rites. [2]

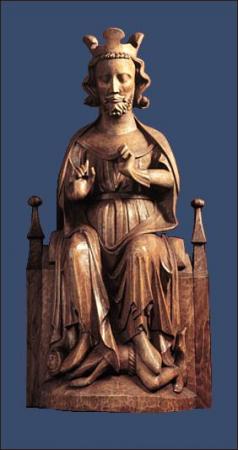

Those who still worshipped the old gods had good reason to flee, for the early Norwegian kings christianised their subjects with the sword. One of these was Olav. In his lifetime he was called “Olav the Fat”, but now he is known as “Saint Olav”. This was the raider-turned-king whose spectacular success in getting baptisms earned him sainthood.

Olav spent his youth abroad fighting the Danes in England as a mercenary. (He opened up the Thames to the longboats of the raiders by pulling down the bridge, a feat which is still remembered in the song London Bridge is falling down). Later he served the Duke of Normandy, plundering on his behalf. His temporary overlord, Richard II, belonged to an already christianised Norse dynasty and in his presence Olav was baptised. Becoming Christian was the necessary step if Olav wanted to advance from pagan Viking raider into the rank of the converted kings. "Viewed strategically, not to have let himself be baptised and christianised would have been foolish in his situation." [3]

In 1015 Olav returned to Norway with four bishops and several priests. He fought his way to kingship, eventually issuing coins with the title "rex". As a king he now had an army to help him in his holy works. With his troops waiting, he'd tell a local leader: “Either accept Christianity, or fight this very day”. [4] Those who displeased him, Olav ordered to be blinded or had their tongues cut out. [5] People converted in droves.

The arrival of the new religion brought many technical skills to Norway from in other parts of Christendom. The clerics introduced the cultivation of vineyards and winemaking, techniques in metalworking and milling and even fishing with nets. [6] Perhaps most important was the introduction of written documents. These were largely a clerical monopoly and made the Church indispensable in state administration. It also changed the way facts were verified. Instead of the traditional method of relying on the testimony of witnesses, appeal was now made to writing on parchment and the monks had long experience in forging this. The Church now controlled the past.

Through the Christian kings, the Church also controlled society. Saint Olav and the other early kings turned the pagan assemblies, the things, into enforcers of Church doctrine and made them the forerunners of the Inquisition. The things passed laws condemning whatever the Church disapproved of, set up a system of informers and meted out harsh sentences to anyone caught violating the myriad of complex religious rules controlling daily life. Through the thing the Church enforced rules on everything from days of fasting and other food restrictions (more than 40 per cent of the year) [7] to rules on when married couples were allowed to have sex. To sweeten the deal, the king received a shared of the fines that were levied by the things. “The Norwegian laws provide a picture of a well-structured system of information, control and punishment." [8]

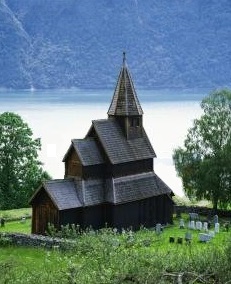

At the local level, below the things, clerical control came to be exercised by a network of churches. By 1350, when the Black Death swept over Norway and brought construction to a halt, some 1000 wooden “stave churches” had been built, of which 28 survive today. [9] (They are named from their load-bearing corner posts called “staves”, filled in with walls of vertical planks raised on sills to keep them from rotting.) Most of these were not village churches but, to root out the old gods, were built deep in the woods at former heathen offering places.

The oldest of these stave churches to have survived is at Urnes (c. 1130). The carving on its portal shows how missionaries used pagan parallels to ease the converts into Christianity. The scene is generally considered to portray Christ overcoming Satan. However, here Christ is depicted as a “lion”, that looks like one of the intertwined monsters carved on Viking ships, and his adversary is a “snake” like the Midgard Serpent, the enemy of the old Norse gods. [10]

By 1152 Norway had enough churches to split off from the general Scandinavian archbishopric in Lund and form a Norwegian Church directly under the pope.

By 1152 Norway had enough churches to split off from the general Scandinavian archbishopric in Lund and form a Norwegian Church directly under the pope.

To do set up a new Church province, a symbol of the pope's authority was needed and Thomas Breakspear, the papal legate, brought the required pallium from Rome. (For a picture of an early pallium see the fringed scarf displayed by the last Anglo-Saxon archbishop.) Centuries earlier Gregory I had begun to insist that every archbishop receive this badge of office from the pope before he could carry out his duties. The requirement of the pallium meant that the pope controlled the appointment of archbishops. However, once a king was granted an archbishopric in his land, the ruler tended to take over the Church organisation and appoint as bishops “king's men” who were loyal and obedient. [11]

To prevent the king taking control of the national church, concordats strictly limited royal influence. Article 4 of the Norwegian concordat insists that in the appointment of bishops and abbots “no power, no influence, no authority from king or prince should intervene”. Only “their most Catholic majesties” of Spain and Portugal, whom Church relied on to carry out missionary activities in their far-flung empires, were able to insist on a regal right to appoint bishops, (the patronato or padroado)

To prevent the king taking control of the national church, concordats strictly limited royal influence. Article 4 of the Norwegian concordat insists that in the appointment of bishops and abbots “no power, no influence, no authority from king or prince should intervene”. Only “their most Catholic majesties” of Spain and Portugal, whom Church relied on to carry out missionary activities in their far-flung empires, were able to insist on a regal right to appoint bishops, (the patronato or padroado)

Rulers, however, were not the only ones who threatened the power of the Church. Its own priests could also erode its position. A married priest naturally wanted to pass on his job and his property to his son and this threatened the steady accumulation of land by the Church, which was the normal result of gifts and bequests by those in fear of the hereafter. To stem the loss of Church property to the children of priests, in 1123 the First Lateran Council forbade marriages for priests. Before this, if a cleric married, the marriage was considered illicit and sinful, but still valid. However, after the celibacy ruling, such a marriage was declared null and void and priests who were already married were commanded to leave their wives.

Over the course of its long career, the Vatican has found the most effective ways to ensure its temporal power by holding in check those who might weaken it. These means included vows to bind priests and concordats to bind kings.

Notes

For an excellent and detailed online account, see Thomas B. Willson, History of the church and state in Norway from the tenth to the sixteenth century, 1903, especially Chapter 14:

“Magnus Lagaboter and the Tonsberg concordat”, pp. 209-224.

* From the Borgarthing Law (c. 1050), Sanmark, ibid., p. 158. For present-day Icelandic belief in “elves”, see Sarah Lyall, “Building in Iceland? Better clear it with the Elves first”, New York Times, 13 July 2005. http://www.nytimes.com/2005/07/13/international/europe/13elves.html

1. D.M. Murdock, "Pre-Christian Temple Discovered in Norway", Yahoo Contributor Network,

19 March 2012. http://voices.yahoo.com/pre-christian-temple-discovered-norway-11121380.html?cat=37 This contains a translation of the following article:

“Fant hedensk helligdom uten sidestykke,” Aftenposten, 23 December 2011. http://www.aftenposten.no/nyheter/iriks/Fant-hedensk-helligdom-uten-sidestykke-6727104.html#.T2Nutexp6l2

2. For a summary of the heathen rites in Mære,Trøndelag (Central Norway) whose church is built atop a pagan site, see "Blót", Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bl%C3%B3t#M.C3.A6re.2C_Norway

For the source in the Icelandic saga, see Snorri Sturluson, Heimskringla or The Chronicle of the Kings of Norway (c. 1230), trans. Samuel Laing (London, 1844), Hakon the Good's Saga, 16. "About sacrifices". http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Heimskringla/Hakon_the_Good%27s_Saga#About_Sacrifices.

3. Øystein Morten, Jagten på Olav den hellige, 2013, p. 69.

4. Heimskringla/Saga of Olaf Haraldson/Part IV, 17. Dale-gudbrand is baptized. http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Heimskringla/Saga_of_Olaf_Haraldson/Part_IV#Dale-gudbrand_Is_Baptized.

5. Heimskringla/Saga of Olaf Haraldson/Part II, 26. Mutilating of the Upland Kings. http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Heimskringla/Saga_of_Olaf_Haraldson/Part_II

6. Alexandra Sanmark, Power and Conversion - A Comparative Study of Christianization in Scandinavia, University College London, Ph.D. Thesis, 2002, p. 48.

6. Sanmark, p. 260.

7. Sanmark, p,251. Here he is talking specifically about fasts, but on p. 277 he concludes that “the population was firmly tied into [...] the web of detailed regulations throughout the year”.

8. “An era of churchbuilding”, Fortidsminneforeninga, (The Society for the Preservation of Norwegian Ancient Monuments). http://home.loopme.com/fortidsminneforeningen/sites/fortidsengelsk/go.cfm?id=66847&type=text&lang=nno&path=0i48413i66537i66539i66555i66578i66847

9. Sanmark, ibid., p. 96.

10. Sanmark, ibid., p. 55.