Money for silence

Money for silence

Former Bishop of Regensburg, Gerhard Ludwig Müller, didn’t tell the police about a priest in his diocese who abused children, but sued the journalist, Stefan Aigner, for calling the secret payments to victims “hush money”. The Bishop got a court to order the deletion of a summary of his actions from a Spiegel article. Here is a translation of a full account of this case which escaped the ban.

Update: In 2012 who, of all people, was appointed by the Pope Benedict to handle Vatican abuse cases? Pope Francis then let him stay on before finally sacking him in 2017. During the five-year tenure of this notorious priest-shuffling Cardinal 2,000-case backlog built up, which effectively gave the accused abusers a reprieve.

Priest-shuffling German bishop says payment was not “hush money”

Introduction. Evidence of child abuse in the Bavarian Diocese of Regensburg was suppressed, yet any dissent among the faithful brought censure. The Bishop was notable for his zero tolerance policy of deviation from any Vatican position. Bishop Müller is considered to be “on the extreme right of his church, with a submissive gaze towards Rome, where his actions are more or less openly supported”. [1] In 2010 his diocese brought to court Germany’s best regarded news magazine, Der Spiegel, as well as two local bloggers. [2] The next year, however, the State of Hamburg appeals court overturned the ruling against one of the bloggers in the name of free speech. [3]

Has this diocese more to hide? Could it be that the bishop's aggressive legal stance was also intended to forestall any investigation of his former choirmaster who still lived in Regensburg — the brother of the Pope? In 2010 allegations of endemic abuse flooded in about the feeder school for Georg Ratzinger’s cathedral choir, and even some about the choir itself. The Pope’s brother claimed to have known nothing about any of it, although he lived and worked with the boys for 30 years. [4]

The court proved strangely naive. In 2010 the Regensburg Bishop Gerhard Ludwig Müller got the Hamburg state court to forbid the media to so much as imply that a payment to the family of boys abused by one of his priests was “hush money”. [5] True, the money was handed over at the same time as the parents signed an agreement to remain silent. However, the Church lawyers had drawn up a clever contract claiming that the silence was the wish of the parents, and the court took this at face value. The agreement signed in 1999 stated, “In the well-understood interest of the children and at the expressed wish of the parents it will be granted to maintain silence.” [6] From this the court concluded that the aim was to make sure that the Church kept silent about the abuse.

The court also apparently ignored the mother’s statement, made public the week before the judgement was handed down. She told Bavarian State Radio that she interpreted this payment unequivocally as hush-money, even though “it was justified as being for the protection of the children, so that they wouldn’t be denounced, because that would be fearfully painful for them”. [7] She also said that at the time she was especially angered that the Church rejected a passage in the contract in which she wanted to have stated that the priest would never again work with young people. Later the same priest was shifted by the Bishop of Regensburg to a village where he proceeded to abuse many more children.

As a result of the 2010 ruling, a long and well researched article about clerical abuse in Germany was removed from the website of the highly regarded German news magazine, Der Spiegel, leaving a curious gap between pages 59 and 72. [8] It contained a few sentences about “priest-shuffling” by the Regensburg bishop, who followed the usual pattern of moving the abusive priest to a smaller and more remote parish. [9]

Read the fuller article that escaped the ban. Luckily, there’s a much fuller account of this case in an earlier Spiegel article, which is translated below. It begins with the festivities to welcome the new priest held by the unsuspecting villagers. They knew nothing of his past: in the account of his life published in their parish letter the name of the town where he had previously molested children had been carefully removed. The secrecy enabled him in his new parish to begin abusing an eleven-year-old altar boy and continue undiscovered for more than two years. [10] This prompted Catholics from his diocese to hold demonstrations in front of the court and the cathedral, with signs such as “Bishop Müller — that's enough”. [11] His Excellency, however, made no apology. [12]

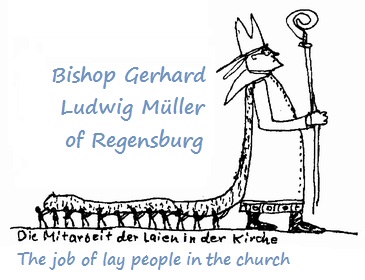

The Bishop's protection of the paedophile priest contrasted with his treatment of most groups of Catholic laymen. In 2006 he cut of funding for the largest of these, the Central Committee of German Catholics, which had called for democratic structures in the Church. He also suppressed the Diocesan council of Lay People and thirty-three other Catholic organisations. [13] One of his flock in Regensburg, Gerhard Schmidt, did this impression of the Bishop's stance: [14]

Money for silence

By Conny Neumann and Peter Wensierski

“Schweigen gegen Geld”, Der Spiegel, 17 September 2007

Through an unethical offer on the edge of legality the Church has tried to protect a child-abuser in a cassock — which apparently enabled him to assault altar boys again.

His new flock had greeted him with a symbolic gift: As the priest Peter K. began his service in September 2004 in Riekofen near Regensburg, they presented him with a large floodlight. He was to bring the light of God to Riekofen and also look into the dark corners.

However, the Catholic priest apparently liked to seek out dark corners for himself — in order, as witnesses maintain, to assault altar boys. At the end of August [2007] on his way to a holiday, he was arrested by investigators from the Criminal Police because of the danger that he might flee.

Now the man of God sits behind bars, and the village of Riekofen is in shock. This case in the Diocese of Regensburg could become one of the most serious sex scandals among the German Catholics. The charges against the Regensburg Bishop Gerhard Ludwig Müller are massive. Der Spiegel has been shown documents which prove that his Diocesan administration — operating on the edge of legality — tried to hush up the child abuse: Silence was to be bought with money. One of the abused youths accuses the churchmen: “They aren't concerned with the victims but only want to ensure that nothing is made public. That hurts.”

For K., now 39, had already attracted attention years before as a child abuser. Just an hour’s drive away in the town of Viechtach 46-year-old Johanna T. can hardly believe what has now happened in Riekofen. More than once she had warned the church in Regensburg against exactly this. Johanna T. clenches her fists when she thinks about Father K. and the behaviour of the Diocese: “The concealment and cover-up right from the beginning” makes her angry.

K. had already assaulted her own sons at Easter 1999: “We joined other families for a social hour at the [Catholic charity] Kolpinghaus and left the care of the children to Chaplain K.”, she said. The priest played hide-and-seek with the children and lured them into especially remote corners.

In the course of this K. besieged her nine-year-old son and groped his genitals. Then he demanded that his twelve-year-old brother Benedict undress. The intimidated youngster obeyed the priest. K. played around between Benedict’s legs. But Benedict’s eleven-year-old sister saw everything — and on the way home told her parents about the strange game.

The parents complained immediately to the Vicar General. But Johanna T. said that the Diocesan administration in Regensburg discouraged them from laying charges with the police. It preferred to handle the case internally within the Diocese.

Then on 25 November 1999 a legally very dubious agreement was concluded between the family, offender and the Diocesan administration. In the contract, which until now has been unknown to the public, it says: “In the well-understood interest of the children and at the expressed wish of the parents, silence shall be maintained.” Benedict received at the time 4000 Marks, his sister 1000 Marks and the brother 1500 Marks as “compensation” from the priest.

But the mother also demanded from the Diocese a written assurance that the groping priest would not be assigned to youth work again: “I can't sleep properly with the idea that he could destroy the souls of more children.”

The fear was apparently justified. But the lawyer of the Diocese refused to give the assurance. Such a thing could “not be approved by the Diocesan administration” he wrote back to the family. The Church could only promise “that the future deployment of Mr. K. would take place only after careful deliberation”.

Shocked by the groping, the family wanted to at least keep open the possibility of later pressing charges against the priest. But that was also smoothed away by the Diocesan administration: “Because the future pastoral deployment of Mr. K. shall remain exclusively in the competence of the Diocesan administration, whereby in the type and time of the deployment the previous events will be taken into consideration, we cannot accept that ... the right to press charges be reserved”.

Finally the family signed the silence pact.

However, several months later an acquaintance of the father laid charges against the priest, after all. The father had confided in the woman at a clinic. After the assault on his sons he suffered from emotional problems. In July 2000 — after being [quietly] withdrawn from Viechtach — Chaplain K. was given a suspended sentence of twelve months.

At first the T. family did not discover where the priest had disappeared to. And in Riekofen no one suspected where the new priest had come from. For the Diocese had carefully removed his time in Viechtach from his CV in the parish letter.

And already in the autumn of 2000, as the 30-year-old had just begun his three-year probation period, Peter K. had contact with altar boys — contrary to what Bishop Müller's people now maintain. Just last week the diocesan spokesman Jakob Schötz claimed that the Church had waited until after for a four-year therapy before K. was again allowed to work near children.

According to the staff schedule the child abuser was indeed employed in a home for the aged. But he also substituted for many Sunday Masses for the ill local priest. Already in early 2001, as a photo proves, Peter K. celebrated a First Communion in Riekofen and on this occasion blessed at least one boy who, according to witness testimony, later became one of his victims.

In general, the young churchman showed touching devotion to the young: He organised excursions, trips to Hamburg and Rome, on occasion smoked a water pipe with the kids in the cellar. K. managed to recruit about 100 schoolchildren from the parish as altar boys. The parents were satisfied.

Thus it seemed to be a stroke of luck that in 2004 the priest was called to serve as the parish priest of Riekofen-Schönach as successor to the local priest, Helmut Grüneisl. “Even I didn't know anything about Viechtach”, complains Grüneisl. “They should have told me, then many things would have struck me as odd.”

At the end of July [2007] the bomb exploded in Riekofen. The local press reported about the case of Benedict. However, many in Riekofen remained loyal to their priest, some wanted to gather signatures so that K. remained in office. After all, anyone can throw mud, they said. But at Mass the following Sunday K. was absent — a nervous breakdown, he lay in a clinic. There Father Grüneisl visited him: “He assured me then that Viechtach was a one-time thing.”

In the village, however, the parents had become suspicious. Several families brought a psychologist to the parish who provoded care in the Dornrose Organisation in Weiden for abused children. The woman spoke with the altar boys and they began to talk. The testimony of children is certainly not always reliable — not when it concerns matters like these and especially not when they are questioned in a purposeful manner. But the Nuremburg Office of the Public Prosecutor, which investigated K. because of suspicion of abuse, has meanwhile placed about 100 children on its witness list.

The members of the parish council are only sure of one thing: Since 2003, at least according to the children, the priest once again abused boys. At first on excursions, later apparently in his rectory, in which he lived without a housekeeper. K. is said to have invited the boys individually and read from a textbook about sex, says a father who learned of this from altar boys. Then the priest is said to have often asked the boys if they had already had sex. Next he apparently became insistent. The father presumes that “The assaults were likely much worse than what happened in Viechtach”.

That is so far no more than a suspicion: It could still be a matter of a misunderstanding, fuelled by the phantasy of the children. But so far the priest himself hasn't wanted to comment on all this, or explain anything. And for the parents it's a very grave suspicion because it is supported by K.’s past.

This is why many families in the 2000-person parish feel deceived by the Diocese and are disappointed, said members of the church board in a parish letter: The church tried a “cruel experiment” with the souls of children. There is great anger against Bishop Müller.

But Müller’s people consider themselves blameless. The Diocesan administration had a professional opinion, said Müller’s spokesman, Schötz, according to which Father K. was considered to be cured. He said that the churchman underwent therapy and only after that was deployed in Riekofen.

However, the professional opinion amounted only to a statement from the therapist who treated K. And the Diocesan administration studiously ignored the fact that K. had already resumed contact with children in the parish long before there was a professional opinion.

Bishop Müller, a strict churchman who censures his own parish priests for trifles, doesn't see any blame on his part — and has therefore long been unavailable to talk to the people of Riekofen. Instead, he launched a counter-attack. He charged that his critics were mounting a campaign against him.

However, the gentle treatment of child rapists under Müller’s leadership was part of the system. For instance, in the summer of 2004 it was made known that a priest in Falkenberg had assaulted a child. The parents of the victim turned to the Diocese but, according to their testimony, were given a runaround. Only when they went to the police was the priest removed from service.

The Bishop doesn’t want to say anything to Riekofen. But for days he has been telephoning with colleagues and asking for advice about whether he should go there on the 23rd of September [2007] when the new priest is installed. For then he could be obliged for the first time to face the children — and their outraged parents.

Related

For Bishop Müller’s power over academics at a state university:

♦ Controlling professors through the Bavarian Concordat

For state funding of his salary and his ex-choirmaster’s (the Pope’s brother’s) pension:

♦ Millions for the bishops: Why the German state pays the wages for the church

Notes

1. Philipp Gessler, “Kritische Theologen in Regensburg: Die Widersacher”, TAZ, 23 February 2009. http://www.josef-bayer.de/akr/konflikte/taz230209.htm (This article contains several examples of how Bishop Müller tries to enforce Vatican policies and boost the prestige of the Pope.)

2. Landgericht Hamburg, judgement of 10 March 2010 against Der Spiegel (324 O 107/10)

The next month notice was served on the blogger, Stefan Aigner, who had called it “hush money”. http://www.wbs-law.de/allgemein/bistum-regensburg-mahnt-blogger-ab-1499/

Press release from the State Court of Hamburg: “Landgericht Hamburg entscheidet im Rechtsstreit der Diözese Regensburg gegen Spiegel Verlag und Spiegel ONLINE GmbH”, 21 January 2010. http://justiz.hamburg.de/2748022/pressemeldung-2011-01-21-olg.html

3. Oberlandesgericht Hamburg, judgement of 18 October 2011 (Az 7U 38/11)

“Inhalt Missbrauchsfall Riekofen: Begriff ‘Schweigegeld’ ist Meinungsäußerung”, Bayerischer Rundfunk, 19 October 2011. http://www.br-online.de/aktuell/kirche-justiz-missbrauch-ID1294666140909.xml

Christian Solmecke LL.M., “OLG Hamburg: Kein Maulkorb durch Abmahnung von Diözese wegen kritischer Berichterstattung zulässig”, Anwalt24.de, 19 October 2011. http://www.anwalt24.de/beitraege-news/fachartikel/olg-hamburg-kein-maulkorb-durch-abmahnung-von-dioezese-wegen-kritischer-berichterstattung-zulaessig

4. “Pope Remains Silent as Abuse Allegations Hit Close to Home”, Der Spiegel, 15 March 2010. http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/0,1518,683582,00.html

5. Grit Fischer, “Aufgeklärt, abgemahnt - Kritische Berichte über das Bistum Regensburg”, Nord-Deutscher Rundfunk, 19 May 2010. http://www.ndr.de/fernsehen/sendungen/zapp/medien_politik_wirtschaft/kirche240.html

6. “Im wohlverstandenen Interesse der Kinder und auf ausdrücklichen Wunsch der Eltern soll Stillschweigen gewahrt werden.”

Conny Neumann and Peter Wensierski, “Schweigen gegen Geld”, Der Spiegel, 17 September 2007. http://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-52985276.html

7. “Das war begründet zum Schutz der Kinder, dass sie nicht angeprangert werden, weil ihnen das furchtbar peinlich war.”

Missbrauchsfall Riekofen: Schmerzensgeld oder Schweigegeld? Bayerischer Rundfunk, 12 January 2011. http://www.br-online.de/aktuell/kirche-justiz-missbrauch-ID1294666140909.xml

8. Inhaltsverzeichnis, (Index), Der Spiegel, (Heft 6/2010), 8 February 2010. http://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/index-2010-6.html

9. “Inside Germany's Catholic Sexual Abuse Scandal”, Der Spiegel, 2 September 2010. http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/0,1518,676497,00.html

The English version says at the end, “Editor's note: A portion of this story has been redacted due to a legal claim.”

The deleted portions are underlined:

Investigations Drag On Without Results

[...] This coincides with the perceptions of Johannes Heibel, who works for a Germany-wide association that counsels victims of sexual violence and who has worked with people who were abused by priests for many years. “The traditional approach — keep it quiet, cover it up, transfer the offender — is by no means a thing of the past,” he says.

“You aren't concerned about the victims, but mainly about making sure that nothing gets out in the media,” said one abused adolescent, in an accusation directed at Regensburg Bishop Gerhard Müller. A chaplain had grabbed him in the crotch in 1999.

Part 5: A Church Pays Hush Money

Instead of investigating the case and putting the chaplain on trial, the abusive chaplain, acting through the episcopal ordinariate, paid the family what amounted to damages for pain and suffering as well as hush money. Then the man was transferred to another parish, which was not informed about the abuse allegations, and where new cases of abuse were reported in 2003.

10. Christoph Wenzel, “Drei Jahre Haft für den Pfarrer von Riekofen,” Die Welt, 14 March 2008. http://www.wir-sind-kirche.de/?id=129&id_entry=1372

11. “Bischof Müller - es reicht”. http://www.josef-bayer.de/akr/konflikte/mahnwachen.htm

12. Christoph Wenzel, “Drei Jahre Haft für den Pfarrer von Riekofen.” Die Welt, 14 March 2008. http://www.wir-sind-kirche.de/?id=129&id_entry=1372

13. Gudrun Schultz, "German Bishop Stops Funding to Liberal Catholic Organization", Life Site News, 24 February 2006. http://www.lifesitenews.com/news/archive/ldn/2006/feb/06022408

14. Gerhard Schmidt (d. 2007) : “Die Mitarbeit der Laien in der Kirche”, Pipeline, Wir sind Kirche Deutschland (We are the Church) http://kirchenvolksbewegung.de/?id=453&id_entry=783

Translated and edited by Muriel Fraser