The concordat of Magnus the Law-Mender (1277): Introduction and summary

The concordat of Magnus the Law-Mender (1277): Introduction and summary

King Magnus VI, known as "the Law-Mender", issued the first Western secular law code. However, just three years later he was forced by the concordat to hand over to the Church jurisdiction over anything that it considered to fall within its sphere. The list of these "Church matters" in article 2 of this summary shows how the concordat put people back under its laws and its courts.

Who metes out punishment — family, state or Church?

Who metes out punishment — family, state or Church?

When a crime is committed, who has been wronged? If it's seen as an injury to the honour of the family, then it may be avenged in a blood feud. On the other hand, If it's seen as a contravention of the laws of the land, then the state metes out punishment. And if it's seen as a sin against God, then the Church court passes sentence.

Magnus the Law-Mender is pictured here on his traditional high seat between two pillars, handing over a book of laws. This Norwegian king was the first ruler in Europe, (outside the Arab-influenced kingdoms of Sicily and Castile), to introduce a secular law code. "Such a systematic national code, prepared in the king's chancery, was unique in 13th-century Europe." [1]

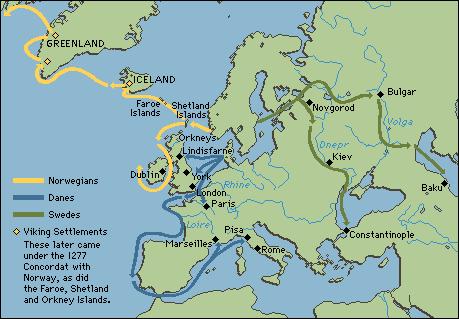

Magnus the Law-Mender, who reigned 1263-1280, drew up unified laws for all of Norway. These replaced the regional patchwork of laws which had enforced the rules of the Church. But the revolutionary feature of Magnus's code was that it introduced the concept that crime is an offense against the state, rather than against the victim or against God. The Church had by this time developed its own law courts and thus Magnus’ law code brought him into conflict with the archbishop. Finally, in the concordat of 1277, the Church of Norway accepted the state's new law books — but only for matters that it felt did not concern it.

When the concordat text was presented to Gregory X at the Council of Lyon in 1274, the pope upped his demands. This has been a concordat negotiating policy of the Vatican for almost a millennium. Whenever the ruler seems weak, as was the case when Austria's Dollfuss came under pressure from the Nazis, the Vatican has a habit of suddenly submitting "improvements" to the draft concordat. [2] The pope seems to have well understood the weakness of Magnus who

was of a more yielding disposition than his father, and above all things wished to live in peace with those around him. His early education, which had proceeded almost on the same lines as if he were intended for holy orders, had made him a man of very considerable learning, and also inclined to listen most favourably to the demands of the Church. [3]

Accordingly, the pope added some new clauses to the draft proposal. These offering the king's crown to Saint Olav on the altar at Nidaros and, in the case of an under-age king, letting the Church govern the country. [4]

The increased demands of the Church allowed it to present the final text of Concordat of Tønsberg as a compromise. The pope gave up his audacious revisions and, in return, (among other concessions), "all cases related to the Church" were to be tried in ecclesiastical courts. This list of the important areas of life to be put under the legal jurisdiction of the Church is summarised in Article 2 below.

Summary of the Treaty of Tønsberg, 1277

(The concordat of Magnus the Law-Mender)

The “Treaty of Tønsberg” (Sættargjerden i Tønsberg [5] is the concordat that was entered into after many years of negotiations in 1277, whereby the royal power, represented by Magnus the Law-Mender (Magnus Lagabøte [6]), and the Church, by Archbishop Red John (Jon Raude), reached agreement on the boundary between the secular and the ecclesiastical spheres of authority. Both parties were to refrain from interfering with each others' elections, e.g. elections of kings and bishops. The Church got approval for the archbishop’s right to issue coins and to hold a court of law including the right to levy fines, and the Church also received tax exemption.

The “Treaty of Tønsberg” (Sættargjerden i Tønsberg [5] is the concordat that was entered into after many years of negotiations in 1277, whereby the royal power, represented by Magnus the Law-Mender (Magnus Lagabøte [6]), and the Church, by Archbishop Red John (Jon Raude), reached agreement on the boundary between the secular and the ecclesiastical spheres of authority. Both parties were to refrain from interfering with each others' elections, e.g. elections of kings and bishops. The Church got approval for the archbishop’s right to issue coins and to hold a court of law including the right to levy fines, and the Church also received tax exemption.

The Treaty, with its royally accepted formalisation of rights, can be understood as the high point of the power and independence of the Church in Norway and as such has a central position in Norwegian history. The agreement is written in Latin and takes the form of a treaty (Latin: compositio [7]). It is an example of how the king enters into an agreement on equal terms with another power within his own territory, and so underlines the equality between the king and the church. Such a concordat was new in Norway, but not elsewhere in Europe.

When King Magnus Lagabøte died in 1280, the nobility in the regency government of the 12-year-old Eirik II Magnusson tried to revoke the agreement by, among other things confiscating Church property. In 1287, during this conflict, they exiled the archbishop Red John (Jon Raude) and the bishops Andres of Oslo and Torfinn of Hamar.

After two years of conflict, it was resolved when the king came of age at 14 and decided that the agreement should be respected, but without it being restored as a valid legal document. This was then a royal decree and not in the form of an agreement between equal parties like the Treaty of Tønsberg.

Summary

In the preface of the Treaty it was stated that a dispute had arisen between King Magnus Håkonsson and Archbishop Jon Raude, and that this was the background for the meeting and the concordat.

In the preface of the Treaty it was stated that a dispute had arisen between King Magnus Håkonsson and Archbishop Jon Raude, and that this was the background for the meeting and the concordat.

By ancient custom secular judges had handled cases that under Canon Law should be handled by Church courts. The Church had accepted this in silence to avoid conflict, but the archbishop wanted to return this to the Church organisation. In addition the Church wanted to start using privileges that over time had been reduced due to lack of usage. This specifically applied to the privilege of “crown offering and submission” (kroneofring og underkastelse) bestowed by a certain Magnus Erlingsson [8], who was said to be king of Norway. This was a specific reference to King Magnus’ promise to offer himself and his kingdom by offering his and all his successors crown to St. Olav in the cathedral in Nidaros. [9] The Church also objected to a decree specifying election of the Norwegian king. Finally the archbishop presented a demand for the archbishop and the bishops to have a first vote among other voters in the elections of kings.

The agreement was made on the initiative of king Magnus “as a peace-loving and righteous sovereign” at the [St.] Lawrence Mass (9 August) 1277 in the church at Tunsberghus fortress. The agreement describes mainly the privileges accorded to the Church, and dwells less on its obligations.

Its articles are as follows:

1. The archbishop had to surrender any right, if he had any, at the elections of kings, subjection and crown sacrifice. But if there was no candidate to the throne, the archbishop and the bishops should get the first and most important votes among the other voters. They would the have to swear to find the candidate that was best qualified for the throne.

2. In all cases related to the Church the king renounced passing judgement. Church judges should judge unrestricted in such cases. This included cases on: clerical issues, marriage, childbirth, patronage rights, tithes, holy vows, wills, protection of pilgrims visiting St. Olav or other Norwegian cathedrals, matters relating to Church property, sacrilege, perjury, usury, simony, heresy, concubine life, adultery, incest and everything else that might fall under the purview of the Church. The king however got support for that in cases where it was custom or valid law that fines should be paid to him

3. The archbishop and the bishops got permission to appoint people to chapels founded by the king. It was not necessary to present [them] or get the king’s approval for such appointments.

4. The king should not have any influence in the appointment of abbots and bishops. Before the appointment the candidate should nevertheless be presented to the king.

5. Bishops, abbots and other clergy should be exempted from leidang [10] travel or pay leidang tax. The bishop could nevertheless consider the specific situation and give exemption for clergy to perform these duties.

6. It should not be permitted for the king to change the country’s laws and fines so that it would cause a loss for the Church.

7. The archbishop got permission to buy falcons.

8. The king should pay tithes on his landed property, according to canonical regulations.

9. The archbishop was awarded the income from 30 lester [11] of flour that was shipped to Iceland.

10. The archbishop was awarded the customs duties from one ship from Iceland each year.

11. All pilgrims should have protection. Those who harmed them should be convicted by a Church court.

12. The archbishop got 100 of his men exempt from leidang travel, warfare, mustering [of troops], ship duty and from leidang duty.

13. Each of the bishops in mainland Norway should have exemption from leidang duty for 40 of his men.

14. Each parish priest should be exempt from the leidang tax. The priests were also exempt for leidang duty for two of his men, and one from the household should, by the priest’s designation, be exempt from royal warfare.

15. If any of the archbishop’s 100 men injure each other on his estate or on his ship, the archbishop shall give the judgment. If they injure each other at another place, they could chose between the court of the king and that of the Church, and the fine was to be shared between the king and the archbishop.

16. The archbishop, the bishops and other clerics were exempt from the trade embargo.

17. The archbishop was awarded the right to make coins.

Source:

“Sættargjerden i Tønsberg”, Wikipedia, 2008.

http://no.wikipedia.org/wiki/S%C3%A6ttargjerden

Translated by Roar Johnsen

Notes

1. Charles Joys, "Norway: Conflict of church and state", Encyclopedia Britannica, 2013-11-11. http://global.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/420178/Norway/39305/Conflict-of-church-and-state

2. Wolfgang Huber, "Concordat negotiations: Austria 1933", Concordat Watch. http://www.concordatwatch.eu/topic-17781.834

3. http://www.archive.org/stream/historyofchurchs00willrich/historyofchurchs00willrich_djvu.txt

4. Ibid.

5. Sættargjerden: the making of a treaty, agreement, peace transactions.

6. Lagabøte: descriptive: He who fixed (repaired) the laws. More on him in English at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magnus_Lagabøte

7. (Latin) compositio -onis f. [putting together]; of opponents, [matching; composing, compounding; orderly arrangement, settlement].

8. Magnus Erlingsson was the first leader to be crowned king of Norway. This was in 1161, more than a century before the concordat and therefore there were no witnesses left to dispute this remarkable Church claim.

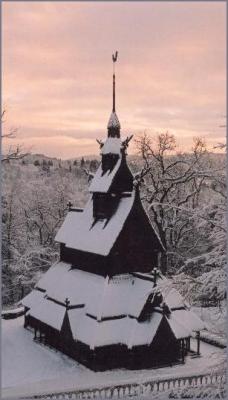

9. How Nidaros cathedral looks today. For a similar custom in Spain, see http://www.concordatwatch.eu/site-845.834

10. Leidang: Duty of peasants and free citizens to take part in the naval activities of the king or to pay taxes to be relieved from this duty.

11. Lest (pl. lester): Measure of volume, usually 12 barrels